My research explores the overlap of ideas, culture, and policy in China, especially in the PRC’s interaction with the world

My first journal articles look at the politics of language (1989) and film (1993) in China.

Contingent States (2004) is the first monograph to use poststructuralism to interpret Chinese foreign policy, and it examines how the PRC bases its foreign relations on a strict inside/outside understanding of the world that places China at the center of civilization, and sees other countries as barbarians. Contingent States shows how hard Beijing has to work to construct and enforce these ideological boundaries, while it also polices alternative views of China and the world.

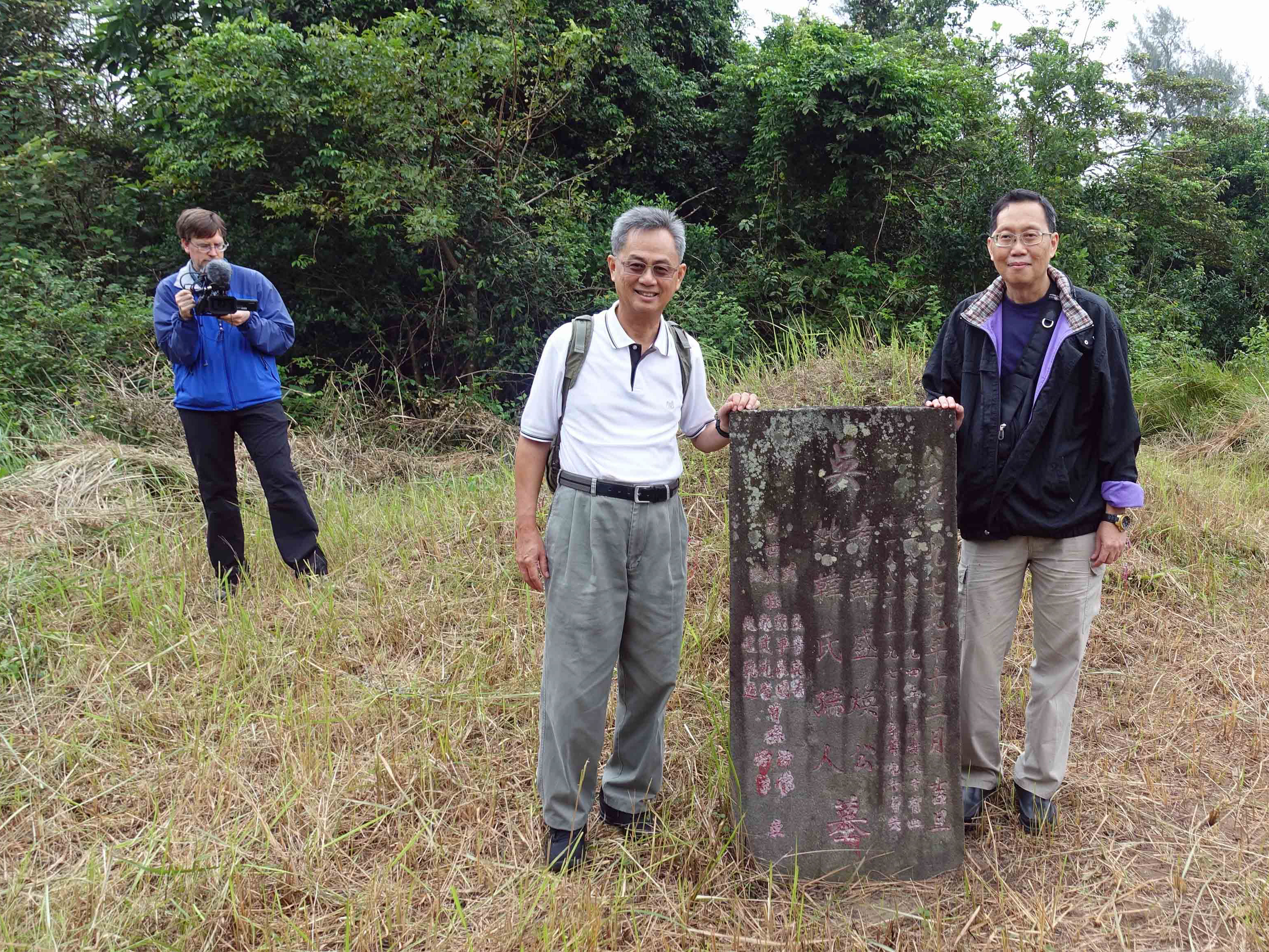

China: The Pessoptimist Nation (2010) develops this analysis to examine Chinese nationalism as a dynamic that combines a superiority complex with an inferiority complex: i.e. a combination of pessimism and optimism where national security is closely linked to nationalist insecurities. To chart the trajectory of its rise, the book shifts from examining China’s national interests to exploring its political aesthetic of “national humiliation.”

Rather than answering the standard social science question “what is China?” with statistics of economic and military power, the book looks to the official historiography to ask “when” is China, to cartography to ask “where" is China, to ethnography and gender to ask “who” is China, and concludes by exploring “how” to be Chinese in the 21st century.

While many say that nationalism was constructed by the state in the 1990s as a reaction to the end of the Cold War, Pessoptimist Nation draws links between China’s struggle for identity and meaning in the early 20th century and in the 21st century. In this way, China: The Pessoptimist Nation shows how the heart of Chinese foreign policy is not a security dilemma, but an identity dilemma.

Click here for an early article (2004) that puts China's nationalist insecurities in the context of global theory and experience.

Research for China: The Pessoptimist Nation was supported by fellowships from the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center

Rather than looking to the past, China Dreams (2013) examines how “citizen intellectuals” in China took advantage of the relative openness in 2009-12 to think about China’s future as the world’s future. While previous generations worked to “save China,” this elite explained how a “China model” could save the world.

China Dreams explores the grand aspirations and deep anxieties of elites in politics, economics, culture and IR, and was the first analysis to highlight the importance of the “China Dream,” which soon became Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s signature policy narrative.

Research for China Dreams was supported by a grant from the Leverhulme Trust

I have written about Chinese soft power in the co-edited volume China Orders the World: Normative Soft Power and Foreign Policy (2012), which brings together the three top proponents of Chinese-style IR theory (Zhao Tingyang, Qin Yaqing, Yan Xuetong) and other analysts. The Woodrow Wilson Center supported research for China Orders the World.

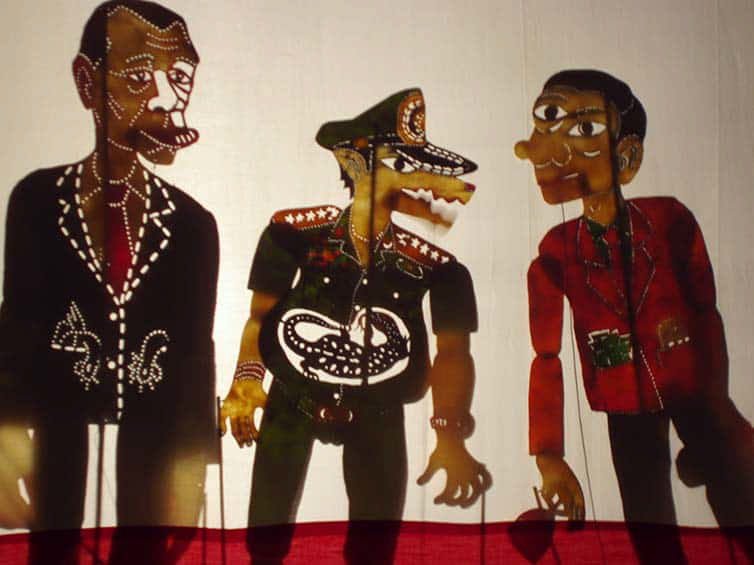

Soft power under Xi Jinping is considered in terms of diplomacy in China’s negative soft power (2015), in terms of art, politics, and resistance in Ai Weiwei (2014), and in terms of Beijing’s quest for normative global power through the Belt and Road Initiative in China’s Asian Dream (2016).

While much of my research uses sophisticated theory to interpret Chinese politics and policy, Sensible Politics (2020) reverses this to explore how Chinese concepts, practices, and experiences can be used to analyze more general issues in politics and international studies. It explores Chinese art to rethink aesthetics and resistance, it uses Chinese maps to develop the idea of map-fare (cartography for strategic purposes), it considers Chinese veils and beauty pageants to question established critiques of Orientalism, it travels to the Great Wall of China to rethink Trump’s Wall, it looks to classical Chinese gardens to discuss civil/military relations, and it examines how the PRC’s surveillance model is becoming the norm in much of the rest of the world.