Sykes-Picot map (1916)

Visa page of the passport of the People's Republic of China (2012)

Complete All-under-Heaven map of the Eternal Qing Great State (1811) Click for high-resolution image

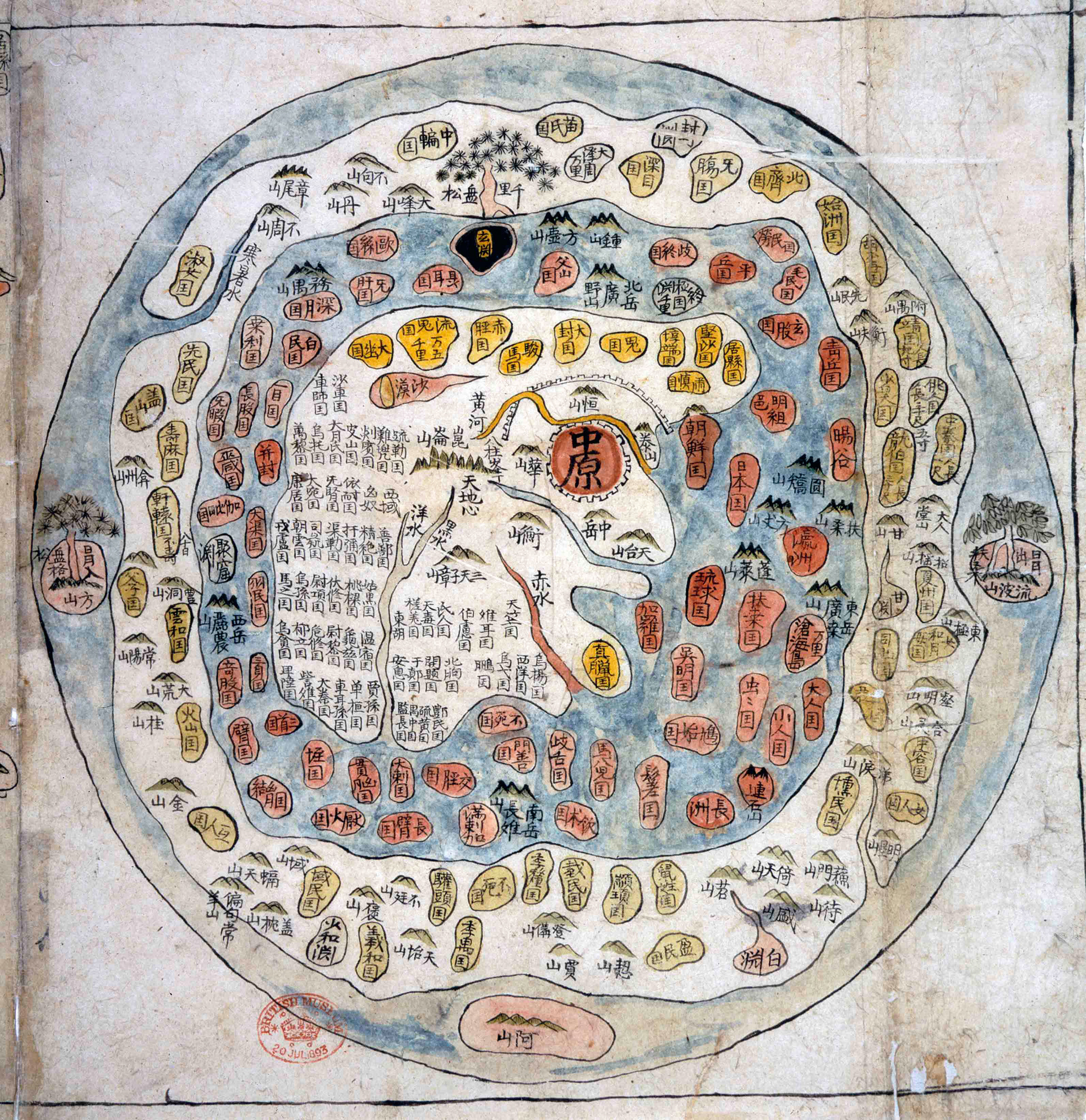

Ch'eonhado (All-under-Heaven map) (Korea, 18th century) Click here for high-resolution image

Korean Atlas: Page 1 (on right) All-under-Heaven map & Page 2 Map of Ming dynasty China Click here for high-resolution image

Map of Civilization and Barbarism (1137 CE, rubbing from stele) Click here for high-resolution image

Map of the Republic of China (1912) Click here for a high-resolution image

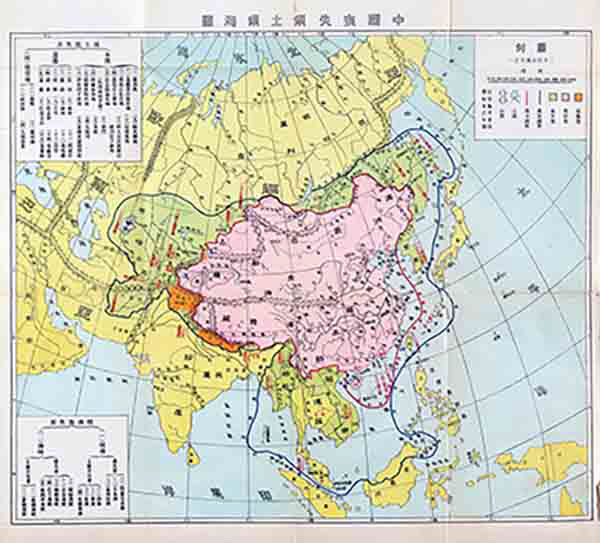

Map of China's lost land and maritime territories (1927) Click here for a high-resolution image

Map of China's National Humiliation (1927, English translation) Click here for a high-resolution image of the original map

"South Seas Islands Location Map" (1947) Click here for a high-resolution image

Maps of a Century of National Humiliation in Modern China (1997/2005) book cover